|

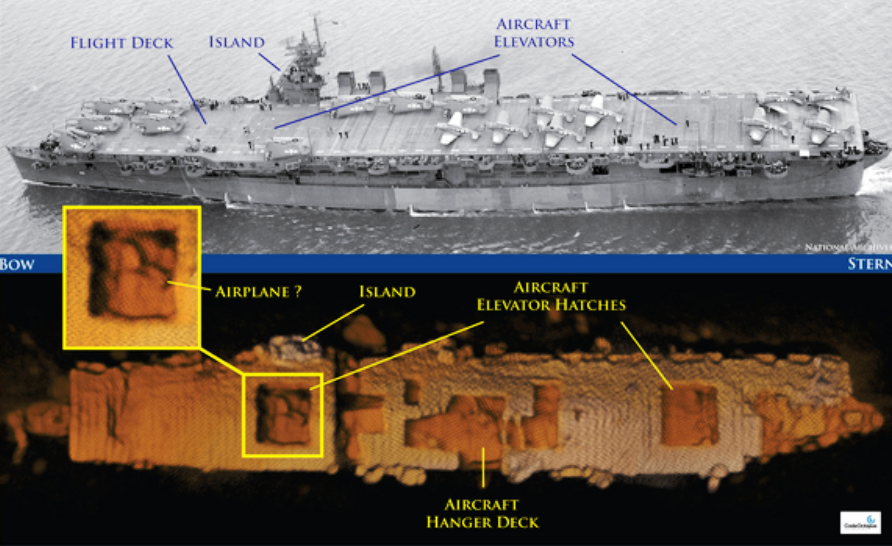

The U.S.S. Independence, a WWII-era aircraft

carrier, has been discovered beneath 2,600 feet of water off the coast of the

Farallon Islands.

This image from NOAA depicts the Independence

as it appeared during its wartime service and a sonar image of the ship at rest

at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, upright and mostly intact. (Courtesy NOAA)

HALF MOON BAY -- In a ghostly reminder of the Bay Area's nuclear heritage,

scientists announced Thursday they have captured the first clear images of a

radioactivity-polluted World War II aircraft carrier that rests on the ocean

floor 30 miles off the coast of Half Moon Bay.

The USS Independence saw combat at Wake Island and other decisive battles

against Japan in 1944 and 1945 and was later blasted with radiation in two South

Pacific nuclear tests. The Navy deliberately sunk the contaminated ship in 1951

south of the Farallon Islands.

The rediscovery of the USS Independence offers a fascinating glimpse into

American military history and raises old questions about the safety of the

Farallon Islands Radioactive Waste Dump -- a vast region overlapping what is now

a marine sanctuary where the federal government dumped nearly 48,000 barrels of

low-level radioactive waste between 1946 and 1970.

The expedition to locate and survey the Independence was led by the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with help from the Navy and Boeing,

which mapped the wreck last month using a robotic underwater vehicle equipped

with cutting-edge sonar capable of producing three-dimensional images.

The images, which show the hull of the ship remains remarkably intact, suggest

the Independence lived up to its nickname, "The Mighty I."

The 623-foot-long ship took a remarkable degree of punishment over its 10-year

career, said NOAA official James Delgado, chief scientist of the Independence

mission. After World War II, the Independence was engulfed in a fireball and

heavily damaged during the 1946 nuclear weapons tests at Bikini Atoll,

transformed into a floating nuclear decontamination lab while stationed at

Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco, then finally towed out to sea

laden with untold barrels of radioactive waste and scuttled with two torpedo

warheads.

The Independence was sunk on Jan. 26, 1951, and came to rest 2,600 feet below

the ocean surface.

The Navy withheld the location of the wreck for decades, but the U.S. Geological

Survey found its likely resting place while mapping the sea floor in 1990. In

2004, a NOAA ship captured a distant image of what looked like a giant

caterpillar stretched on the bottom of the ocean, said Delgado, who has led a

two-year mission to find and study historic shipwrecks in and around the Gulf of

the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary.

"This ship is an evocative artifact of the dawn of the atomic age, when we began

to learn the nature of the genie we'd uncorked from the bottle," said Delgado.

"It speaks to the 'Greatest Generation' -- people's fathers, grandfathers,

uncles and brothers who served on these ships, who flew off those decks and what

they did to turn the tide in the Pacific war."

Delgado said he doesn't know how many drums of radioactive material are buried

within the ship -- perhaps a few hundred. But he is doubtful that they pose any

health or environmental risk. The barrels were filled with concrete and sealed

in the ship's engine and boiler rooms, which were protected by thick walls of

steel, Delgado said.

The submarine that mapped the Independence got within 200 feet of the wreck, he

said. Scientists tested the vehicle and the water on its instruments for

radioactive isotopes and found only normal background radiation levels, he said.

But word of the Independence survey stirred up lingering concerns about the

nuclear waste near the Farallon Islands, an area teeming with wildlife. Retired

judge and state legislator Quentin Kopp, who many years ago demanded research

into the Navy's disposal of radioactive material off Northern California before

1970, said Thursday that the question of whether the waste posed a risk to

humans and wildlife was never resolved.

"If I were an elected legislator, state or federal, I would be pounding the

table," Kopp said.

Kai Vetter, a UC Berkeley nuclear engineering professor who assisted the survey,

said the ocean acts as a natural buffer against radiation. And the contaminated

sites are small enough that they wouldn't work their way into the broader food

chain, he added.

"The risk here to have a public health impact is extremely small," Vetter said.

Vetter said he hopes to obtain samples of the hull of the Independence in the

next year to analyze the effects of radiation and other forces on the metal.

Delgado said, however, there are no plans to further examine the wreck at this

time.

The Gulf of the Farallones sanctuary is a haven for wildlife, from white sharks

to elephant seals and whales, despite its history as a dumping ground.

Richard Charter, a senior fellow at the Ocean Foundation, was involved in the

creation of the sanctuary back in 1981. He said the radioactive waste is a relic

of a dark age before the environmental movement took hold.

"It's just one of those things that humans rather stupidly did in the past that

we can't retroactively fix," he said.

Article By Aaron Kinney |