|

Susan L. Gibbs of Northwest Washington is

trying to save the ship — one of the fastest built — from the scrap yard. She

hopes she and her Washington-based SS United States Conservancy can turn it into

a tribute to a bygone era and, for someone, a money-making enterprise.

For 18 years, the SS United States has been docked in

Philadelphia across the street from the parking lot of an Ikea store. The ocean

liner has been the object of several “save our ship” quests.

Images -SS United States Conservancy

Susan L. Gibbs, wearing a sleeveless blue dress and sandals,

holds a small flashlight as she descends into the interior of the crumbling

transatlantic ocean liner.

“Watch your step,” says the maintenance worker leading the way.

Past the abandoned crew quarters they walk, their voices echoing, and into the

cavernous room with the empty swimming pool, unused for 40 years. “Here we go,”

she says. “Who wants to dive in?”

A resident of Northwest Washington, she once got lost wandering this ship. “It

was so strange,” she says. “You can get disoriented.”

Farther into the gloom they descend, from C Deck to D Deck, then through a huge

door like that of a giant refrigerator. “It’s over here,” she says — indicating

a floor-to-ceiling metal box in the corner.

The SS United States once made the nation proud as the fastest ocean liner in

the world. Decommissioned in 1969, it has since been deteriorating at a dock in

Philadelphia. Now Susan Gibbs, granddaughter of the ship’s designer, William

Francis Gibbs, is fighting to give the ship new life.

The ship’s morgue: two vacant bays, with doors

ajar, and little slots for the name tags.

Of all the places on the rusting behemoth that Gibbs, 52, is trying to save from

the scrap yard, the morgue may be the most pristine.

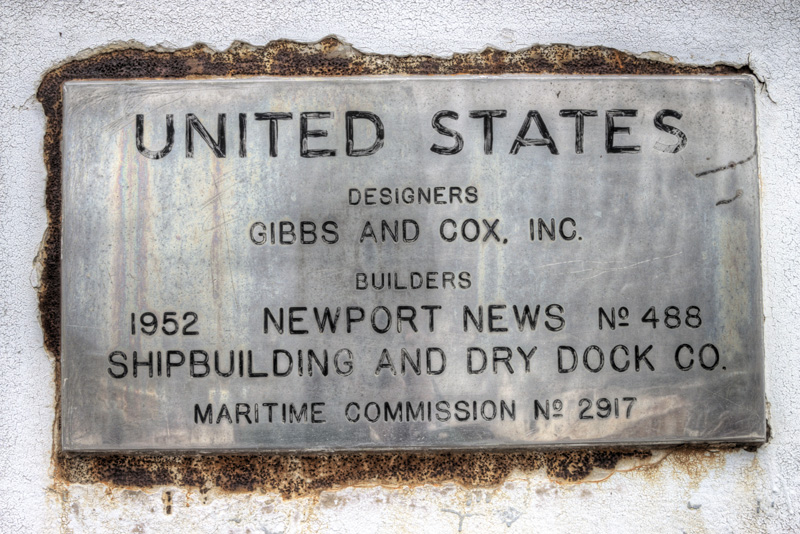

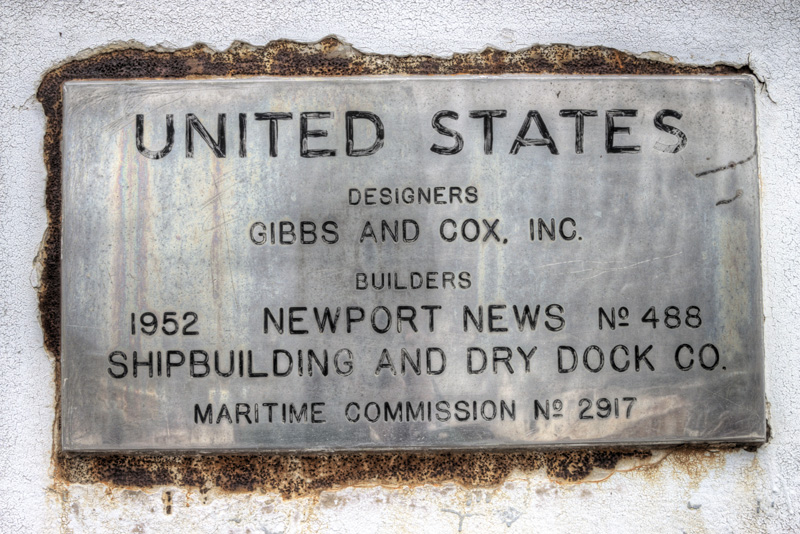

The rest of the 53,000-ton SS United States, which was designed by her

illustrious grandfather, William Francis Gibbs, and launched in 1951, is a

landscape of peeling paint, cobwebs and vanished grandeur.

The legendary vessel was 100 feet longer and 10,000 tons heavier than the

Titanic. It was one of the fastest liners built and the epitome of the suave,

modernist American style of the ’50s.

But it has been out of commission since 1969 — killed by the advent of the

jetliner.

Stripped, bedraggled and moldering on the Delaware River for the past 18 years,

the ship costs more than $60,000 a month just to keep docked.

Now, Gibbs, whose Washington-based SS United States Conservancy owns the ship,

is fighting what may be the final battle to preserve it — as a tribute to a

bygone era and, for someone, a moneymaking enterprise.

The dream is to fix it up so it can be moved to New York, its original home

port, where developers could turn it into a museum, as well as exhibit, retail

or living space.

But it could cost a fortune — upward of $10 million to start and as much as $300

million, depending on how the ship is ultimately used.

The conservancy has owned the ship since 2011, thanks to a donation of $3

million from a local philanthropist, H.F. “Gerry” Lenfest.

Gibbs and her husband have contributed about $2,500 to the project. And Gibbs,

as the conservancy's full-time unpaid executive director, has devoted years to

it.

The conservancy raises money through donations from the public, private

foundations and corporations, and in other ways.

In June, as the group was about to sell off one of the ship’s propellers, cruise

industry executive Jim Pollin, a conservancy member and the son of the late

Washington sports team owner Abe Pollin, donated $120,000, with an offer to

match $100,000 more.

But that money will go fast.

Although the conservancy is optimistic about its negotiations with potential

developers, it has enough docking money only to last into the fall. If

negotiations fall through and docking money runs out, it will have to sell the

ship for scrap.

“It’s now or never,” Gibbs says of the situation. (To contribute - click

here)

A consultant for charitable foundations, Gibbs says she has taken on the task

for posterity and as a way to mend her family saga.

Her grandfather was a legendary but now largely forgotten naval architect whose

name faded along with the era of the great transatlantic ocean liner.

Although a bronze bust of him now sits before the fireplace in her home off

Wisconsin Avenue, for many years she knew almost nothing about him.

His design for the SS United States was his masterpiece.

But she is also trying to save the ship for her late father, Frank, who died of

brain cancer in 1995.

He was the designer’s eldest biological son, and he became a small-town radio

newscaster. But he lived his life in his demanding father’s shadow, Gibbs said,

and rarely spoke of him when she was growing up.

And she is doing it for herself. She said she has become entranced by the ship’s

massive presence and has been moved by all the people who over the years have

had connections to its story.

“This ship has to be saved,” she says. “It’s beyond me and my family. There’s a

potency and a power that lives on. We can’t let it go.”

Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post

By Michael E. Ruane July 31 / (Zoeann Murphy/The Washington Post) |